2025-12-15

2025-12-15

0

0

Dec. 14, 2025, The Wire, by Rachel Cheung, read the original article here

Can artificial intelligence fix China's fragmented public healthcare system?

Earlier this year, on a cold January night, Jiang Xiaoying went from hospital to hospital in a desperate search for a doctor who could treat her 11-year old daughter, Xiaohui. Xiaohui, who had a persistent fever and cough, had spent days hooked up to an intravenous drip at a local clinic near their village home in Jiangxi province. When that didn’t relieve her symptoms, they set off to a larger healthcare center in a nearby town, where a check-up revealed fluids gathering in her lungs and other organs.

The doctor there sent them to a city hospital, which in turn referred them to one in the provincial capital of Nanchang. There, a long surgery finally pulled Jiang’s daughter back from the brink, but what Jiang had thought

was a flu turned out to be an aggressive form of lymphoma that even the best hospital in the province was poorly equipped to treat.

Determined to give her daughter the best chance of survival, they traveled hundreds of miles east to a leading hospital in Shanghai known for its pediatric and oncology care. For nearly a year now, they have stayed at a charity home near the facility. As her daughter endures chemotherapy, Jiang raises funds online to pay her medical bills.

"Simply investing more in underserved areas is not enough. Larger structural inequalities must be addressed. "

Jiang doesn’t know when her daughter’s condition will be stable enough for them to go home, where she has left her six-year-old son in the care of a neighbor. Too young to understand what is happening, he pines for her return and cries on every call. “If my daughter can recover from this illness, then every suffering I’ve had to bear will be worth it,” Jiang says.

Jiang and Xiaohui’s situation highlights one of the perennial challenges for China’s public healthcare system — and the potential transformative effect that artificial intelligence could have on it.

Most medical resources are concentrated in wealthier, urban regions, while access to healthcare in rural hinterlands remains patchy despite years of government efforts to bridge the gap. The Chinese government is hoping that advances in AI can help fix the country’s fragmented healthcare system by overcoming constraints such as doctor and nursing shortages. Aided by AI, an earlier diagnosis may have hastened Xiaohui’s treatment. Under a more efficient system, she may not have had to wait days for a hospital bed.

Last year the National Health Commission issued a 45-page document listing more than 80 scenarios for AI applications, including acupuncture robots, therapy with chatbots rather than human therapists, and tracking children who have skipped vaccines. Last month, authorities released another set of guidelines, the goals of which include the establishment — by 2027 — of pilot zones for experimental healthcare AI and universal adoption of AI diagnostic tools in primary care by 2030.

The policies have spurred the sector into action. By one count, as of May more than 755 hospitals and clinics have deployed DeepSeek the AI model developed by a Hangzhou startup that matches the capabilities of its leading foreign counterparts at a fraction of the cost. One hospital in Xuzhou, a city near Shanghai, introduced an intelligent patient- tracking system in which robots call patients to check on their condition. What took health professionals seven hours to complete now takes 10 minutes, the hospital claimed.

Private companies are eager to tap the market, which is projected to grow from $1.6 billion in 2023 to nearly $19 billion by 2030. Tech firms including Ant Group and JD.com have rolled out services such as digital avatars of doctors that answer online queries. Meanwhile, Baichuan and other small startups are training large language models (LLMs) that will eventually do work currently done by doctors.

TOO SLOW OR TOO FAST?

Local experimentation, such as that in Xuzhou, has long been a feature of Chinese policymaking. But experts are increasingly concerned about the potential consequences of a chaotic rollout of AI in a sector where lives are at stake.

In a commentary published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in June, a group of Chinese scholars warned that the adoption of DeepSeek, which has outpaced regulatory oversight, has been “too fast, too soon.”

“How do you train, evaluate, test and survey an AI model in a healthcare setting? That whole chain has not been clearly defined,” says ophthalmologist Wong Tien-yin at Tsinghua Medicine, under Tsinghua University in Beijing, and one of the authors of the commentary.

Wong, Singaporean national originally from Hong Kong, worries that unchecked use of the technology in healthcare could lead to misdiagnosis and, ultimately, tragic accidents. “That’s the most dangerous fear essentially,” Wong told The Wire China. “That people lose trust in large language models in the healthcare setting and it will therefore set back the integration of AI into healthcare by years, if not a decade.”

The Chinese government has tried for many years to channel more healthcare resources to smaller towns and villages, but a stark disparity remains between the services available to rural and urban populations.

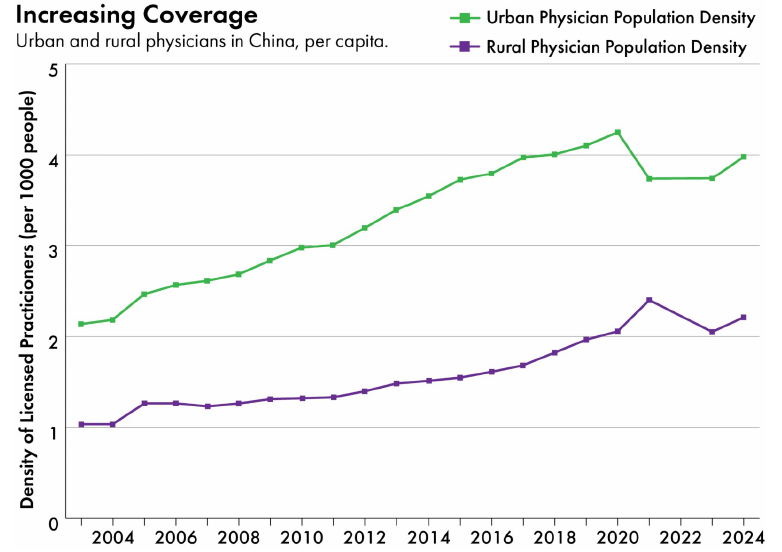

The per capita number of medical facilities, beds and physicians in rural areas are far below the national average. One study, published in The Lancet in 2020, found that as little as one- fifth of village clinicians could correctly diagnose unstable angina, a common heart condition. And even when they did, less than half could prescribe the right treatment. Other research on the competence of physicians in China’s countryside has reached similar conclusions.

Data: Evolution of physician resources in China (2003–2021)

Simply investing more in underserved areas is not enough. Larger structural inequalities must be addressed.

“One major barrier is that it’s very hard to attract and retain qualified providers in primary health care,” says Winnie Yip a health policy professor at Harvard University. “Once a doctor has gone through medical school, they have already built an aspiration to live in the city and to move upward. Only a minority is willing to go to rural or less developed areas.”

"People typically would bypass grassroots healthcare institutions to seek care in urban health centers. The higher demand means more investment in urban healthcare at the expense of rural health case. It creates a vicious cycle."

---- Yanzhong Huang, a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York

Changing the entrenched habits of patients — formed from bitter experience — is equally challenging. With little trust in local physicians, rural residents such as Jiang often prefer to travel long distances to seek medical help for themselves and their loved ones.

As a result, patients from all over the country overwhelm top-tier urban hospitals, which are designed for specialist care but end up shouldering a large portion of the country’s general healthcare burden. According to official statistics, only about ten percent of China’s hospitals are classified as tertiary, which include specialist care, yet they accounted for 27 percent of all visits and half of all patient admittances last year.

A doctor examines patients in a corridor in Zhongshan Hospital, Shanghai

“People typically would bypass grassroots healthcare institutions to seek care in urban health centers,” says Yanzhong Huang a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign, Relations in New York. “The higher demand means more investment in urban healthcare at the expense of rural health care. It creates a vicious cycle.”

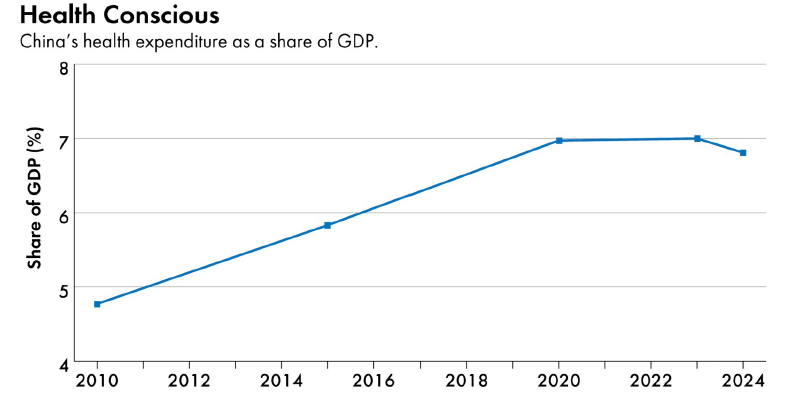

Data: China Statistical Yearbook

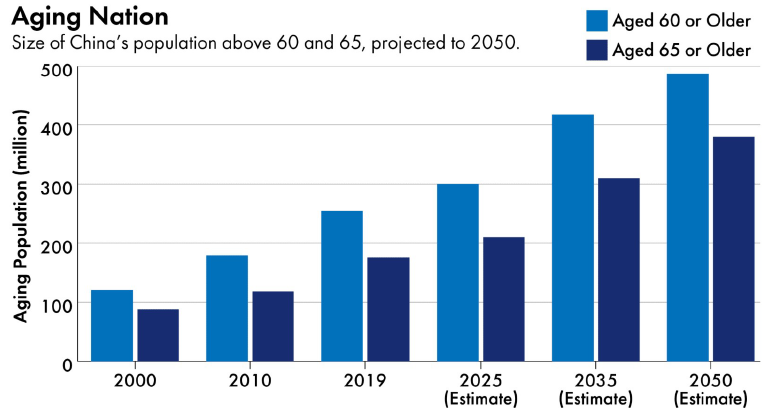

China’s healthcare needs are set to grow exponentially as its population ages. By the end of last year, there were 310 million people aged 60 or above, representing 22 percent of the country’s population. That number could reach 400 million — and 28 percent of total population — by 2040, according to projections by the World Health Organization.

China’s total health expenditure — 9 trillion yuan ($1.3 trillion) or 7 percent of GDP in 2023 — may reach 205 trillion yuan ($29 trillion) by 2030.

Data: National Bureau of Statistics, Deloitte Research

This looming demographic crisis is another factor fueling excitement about AI in healthcare. In more developed economies with relatively robust healthcare systems, such as Singapore, AI applications are icing on the cake. For China, says Wong at Tsinghua Medicine, AI is essential, and not an optional extra.

Wong adds that, in his view, China already has the foundational blocks necessary to take the global lead in AI medicine.

He points out that a country with 1.4 billion people generates a lot of medical data, including data on rare conditions. China’s digital infrastructure is also mature with high mobile phone penetration. And many patients are already accustomed to making doctor appointments or claiming medical insurance online through hospitals’ mobile apps or at digital booths in hospital lobbies. All of these factors make it easier for institutions to collect data and for patients to adapt to AI-powered systems such as virtual triage, where a chatbot assesses patients and directs them to the right care.

Additionally, Chinese people are more trusting of AI. This includes AI in healthcare where 90 percent of Chinese respondents welcome the use of more of the technology, highest among all coutries surveyed by the Philips Future Health Index.

In her newsletter China Health Pulse, Ruby Wang, a China-born, UK-trained doctor and founder of LINTRIS Health consultancy, noted that “China has become a kind of live experimental lab for health AI, in ways that few other countries can match.”

Compared to the UK, where the development of healthcare AI has been slowed by governance and regulatory concerns over privacy and safety, Wang says China more enthusiastic about is the technology’s potential benefits. “It’s not just patients and consumers who are more accepting of tech in healthcare, but also policymakers, clinicians and providers.”

“China is still working on expanding its primary care, but technology is offering new pathways in parallel which can be faster, more cost-effective and scalable all at once,” she adds.

“I strongly believe that AI is the ultimate equalizer,” says Esther Wong, founder of 3C AGI, Hong Kong-based venture capital firm that specializes in AI infrastructure. “In theory, a somebody who lives in a fourth-tier city or the mountains will have the same answer [from an AI model] as someone in Shanghai because that system is trained with millions of data and it’s available for everybody.”

FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE

Qiu Jialin, founder of Hangzhou-based Weimai, wants to extend medical services from clinics and hospitals into

people’s homes. Weimai’s goal, he says, is to make healthcare accessible no matter where a patient is, the same way Taobao made it possible for people to shop over their phones.

Founded in 2015, Weimai provides what it calls a “whole-course” healthcare management service. For as little as 40 yuan ($5.6), a user can consult one of 200,000 doctors on its online platform.

An AI agent, built on LLMs such as DeepSeek and Alibaba’s Qwen, can interpret users’ medical reports. The company has also partnered with nearly 160 hospitals across the country to provide post-surgical patients personalized support, including follow-up consultations and medication guidance.

Backed by Baidu as well as leading venture capital firms such as Source Code and IDG, Weimai is valued at more than $550 million and is preparing for an initial public offering in Hong Kong.

Most of these [AI products] are developed by companies. There’s no way to verify which one is actually doing the right thing… If China is serious about adopting and scaling up AI, there needs to be some development in regulation and standardization.

--- Winnie Yip, a health policy professor at Harvard University

Qiu says AI is not mature enough for doctor consultations and diagnoses — yet. “Users don’t trust [AI] and it doesn’t produce very accurate results, so it’s hard to build a solid business model.” The company focuses instead on post-treatment care, which generates the bulk of its 653 million yuan ($92 million) in annual revenue.

Nevertheless, Qiu is convinced of AI’s potential. “In the past, AI might just have been a tool to execute some standardized procedures. Now AI assistants for doctors can answer most users’ queries,” he says. “Perhaps a case manager on the platform could only deal with a hundred patients in the past, now they can look at 200, 300 or 500 patients.”

In real life, Mao Hongjing, deputy director at a leading hospital in Hangzhou and a highly sought after expert on depression and sleeping disorders, sees about 100 patients a week. But on the AQ app, launched by Ant Group in June, Mao’s AI avatar now handles queries from up to 30,000 patients each day, answering most of them independently.

It is one of 300 such “AI doctor agents” on the platform. Each avatar is trained on the diagnosis records, patient conversations and research output of the real-life physician it represents. Even so, the company says “AQ is positioned as an AI health service, not a clinical diagnostic tool”.

Researchers are also testing the technology in real-life scenarios. In one study, researchers trained a chatbot on phone conversations between patients and nurses who worked at reception in two medical centers. When deployed, the chatbot relieved the heavy workloads of nurse-receptionists. Patients, who found the chatbot more empathetic than its harried human counterparts, were also more satisfied.

In another study led by Wong at Tsinghua Medicine, researchers developed an AI model to screen for diabetic retinopathy, a complication of diabetes that can lead to blindness. Primary-care physicians assisted by the model identified the condition more accurately, and did so in less time. Diabetic patients that took the model’s advice also proved better at managing their conditions.

But rigorous studies like these to test and validate the capabilities of AI models in healthcare are more the exception than the norm. In fact, the two studies also highlight the challenges of building an AI tool that is reliable in medical settings.

“One of the biggest barriers is that there’s very little localized, real-world clinical data. Most of this data is not open-source on the internet,” Wong says. For instance, to train the diabetic retinopathy model, researchers used 21 datasets from screening programmes across seven countries.

And in China, gathering data is an arduous task. There isn’t a single centralized national, or even provincial, repository for clinical data. Even at municipal level, companies often have to go door-to- door to persuade medical institutions to share data that is deemed sensitive. “There never was any practice to share data across hospitals and it was never a requirement, so people tend to hold tight to their data,” says Bruce Liu a senior partner at consultancy Simon-Kucher in Beijing.

When data can be obtained, the next challenge is labeling it. For generic AI models and tools, companies can outsource the drudgery of labelling — tagging, say, a car as “a car” in a street image — to unskilled workers. But for medical LLMs much of the data annotation — labelling symptoms in a doctor’s note or outlining a tumour in a brain scan — can only be done by professionals. Clinical judgement is also inherently subjective and different doctors will often have different interpretations of the same scan or X-ray, let alone symptoms.

For instance, to train the health AI model that underpins AQ, Ant Group incorporated “over a trillion tokens of medical material,” including clinical reports, medical images, and pharmaceutical information. It also enlisted thousands of medical professionals to label the data and review the output.

Yet, even with these thorough steps, there are still fundamental problems that affect machine learning in general. For instance, AI models are prone to hallucination, where they generate false information and convey it with a confidence that misleads its users. They are also susceptible to biases, where they reproduce or amplify harmful stereotypes in their input data.

One study found that Ernie Bot, developed by tech giant Baidu, significantly outperformed physicians in Luohe, a small city in Henan province, in diagnosing asthma and unstable angina, a common heart condition. It had an accuracy rate of 77 percent, compared to 25 percent for physicians, reflecting the huge potential of AI to improve healthcare outcomes in more remote locations.

But Ernie Bot also requested unnecessary lab tests and prescribed inappropriate medication at alarmingly high rates — habits that are also prevalent among Chinese physicians. It may reflect “potential biases in training data,” the researchers noted.

“The current consensus,” Liu says, “is that AI is more likely to be a support system to improve the efficiency or provide a second opinion, but it is definitely not going to be driving the prescription or be responsible for clinical decisions.”

Yip at Harvard adds: “It is unclear whether and how these products have been verified to perform what they claim to do, and that worries me tremendously.

“It is critical that China develops appropriate regulation and standards to ensure that these products benefit the users.”

NEW TECHNOLOGY, OLD PROBLEMS

Technological challenges and ethical concerns aside, AI developers must work out who will pay for their applications and services.

“AI companies involved in the healthcare industry have yet to figure out how they can make money to cover their investments,” says Zhang Hongliang, who runs a Chinese podcast focused on the medical industry.

Most Chinese consumers are not used to paying for software or online services. Some telemedicine platforms, such as JD.com’s JD Health, generate revenue by recommending drugs to patients and taking a cut of the purchase.

Others, such as Weimai, which rely on consumers paying for subscriptions to their services, have struggled to turn a profit. According to Weimai’s prospectus, the company has been in the red for at least three years, racking up a loss of 193 million yuan ($27 million) in 2024 even after scaling back spending on research and development.

Nor is it much easier for companies that sell to other companies rather than individuals.

Healthcare, at its core, is a public good. Public investment plays an important role in supporting innovation. For China, the key challenge is to balance cost efficiency for the public with nurturing a sustainable and innovative AI ecosystem.

--- Esther Wong, founder of 3C AGI, a Hong Kong-based venture capital firm that specializes in AI infrastructure

Such firms typically approach leading hospitals and offer to provide their services for free, so that they can then showcase these “clients” to other hospitals that will actually pay them.

“The powerful hospitals, which every company wants to work with, don’t actually have a habit of paying for these services,” says Jonathan Liu, a Beijing-based medical industry consultant.

Smaller hospitals and clinics, on the other hand, are already contending with falling revenues and government subsidy rollbacks. They cannot easily afford flashy new AI systems.

Simply put, healthcare AI is difficult to scale and the margins are slim. It might be easier for a medical supplier to add AI capabilities to their existing products than it is for a new player such as Tencent to enter the healthcare market, says Bruce Liu at Simon-Kucher.

Some argue that the government needs to step in and make funding available for healthcare AI, particularly in poorer regions. “Healthcare, at its core, is a public good,” says Esther Wong of 3C AGI. “Public investment plays an important role in supporting innovation. For China, the key challenge is to balance cost efficiency for the public with nurturing a sustainable and innovative AI ecosystem.”

There is another area in which industry and government interests are not aligned. At the moment, to generate more income, healthcare providers incentivize doctors to treat more patients, request more diagnostic tests and prescribe more medications even if they are unnecessary. To counter this trend, health authorities are adopting intelligent tools to rein in such behaviour.

AI can be promising in improving competency of care in places where there are not adequate qualified providers, says Harvard’s Yip, but it “may not be very widely adopted in places where there are already qualified physicians, who may see AI as a threat to them or challenging their established pattern of care.

“The healthcare system itself needs to change, to motivate and encourage the doctor to improve quality and access, use AI in a way that achieves these goals, and make them accountable.”